June 12 - Criminal Love: The Case That Struck Down Interracial Marriage Bans

Discrimination Is a Discipleship Issue

This is the day the United States Supreme Court struck down all state laws prohibiting interracial marriage in the landmark Loving v. Virginia case in 1967.

In today's lesson, we will explore how the landmark Loving v. Virginia Supreme Court decision reveals profound spiritual truths about favoritism and discipleship. Does our faith journey allow room for partiality? How might our spiritual growth be hindered by the subtle ways we assign different values to different people? This historical victory for love challenges us to examine whether we've treated discrimination as merely cultural rather than the spiritual issue it truly is.

"If you really keep the royal law found in Scripture, 'Love your neighbor as yourself,' you are doing right. But if you show favoritism, you sin and are convicted by the law as lawbreakers." - James 2:8-9 (NIV)

This Date in History

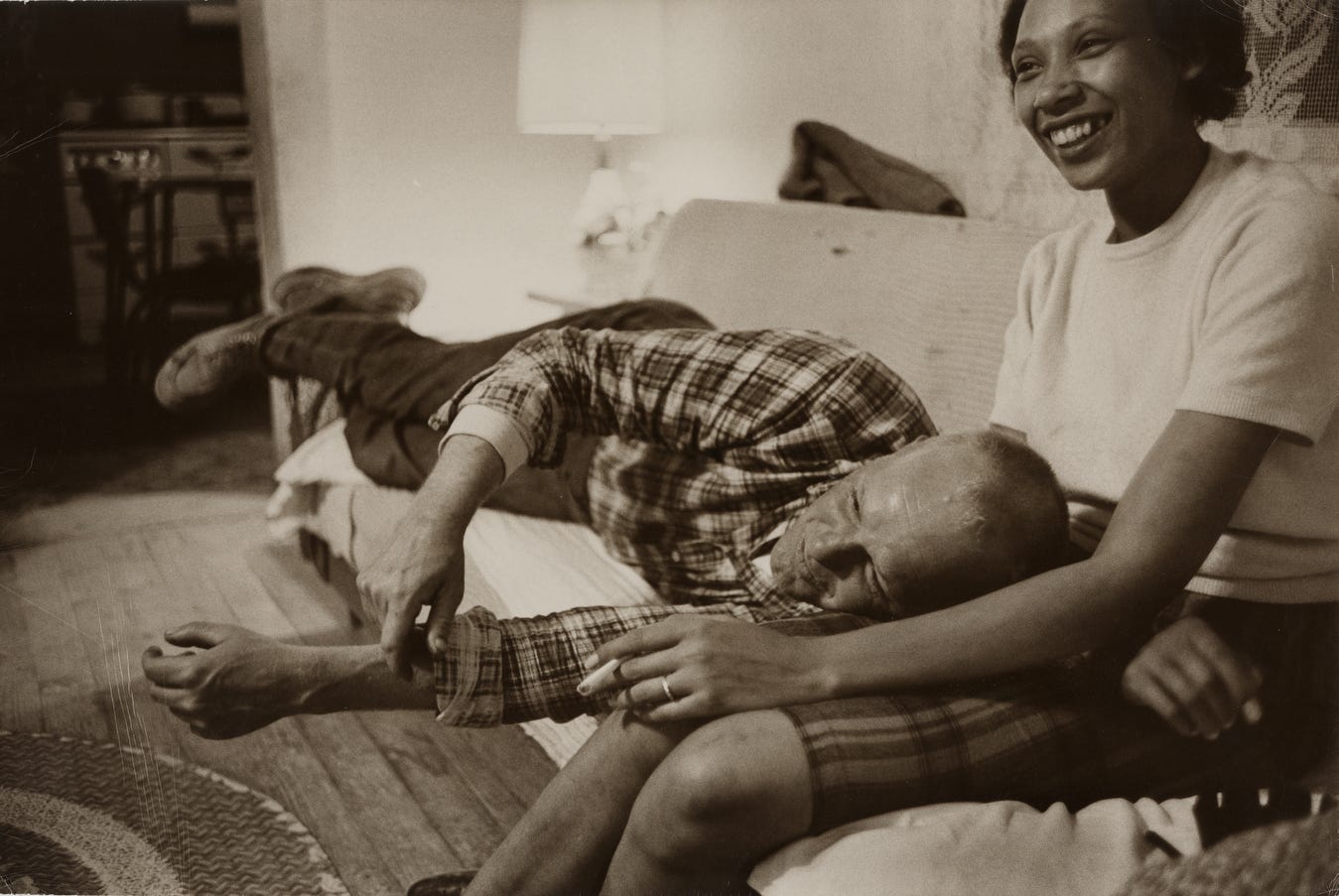

Richard Loving awoke on June 12, 1967, as a criminal in his home state. His crime? Marrying the woman he loved. The small-town construction worker from Virginia had spent nine years fighting for his marriage to Mildred Jeter, a woman of African American and Native American descent. Their wedding certificate, rather than symbolizing their union, had become evidence of their felony conviction.

Richard and Mildred had married in Washington, D.C. in 1958, where interracial marriage was legal, before returning to their hometown of Central Point, Virginia. Five weeks later, local police stormed their bedroom in the middle of the night, arresting them for violating Virginia's Racial Integrity Act. Judge Leon Bazile sentenced the couple to one year in prison but suspended the sentence on the condition they leave Virginia for 25 years. "Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents," declared Bazile. "The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix."

Forced from their home and families, the Lovings moved to Washington D.C., where the isolation became increasingly difficult to bear. In 1963, frustrated by their inability to travel together to visit family in Virginia, Mildred wrote to Attorney General Robert Kennedy for help. Kennedy referred her to the American Civil Liberties Union, which took up their case. Attorneys Bernard Cohen and Philip Hirschkop agreed to represent the Lovings pro bono in what would become a watershed civil rights case.

The Lovings were a quiet, reserved couple thrust reluctantly into the national spotlight. Richard, a man of few words, instructed his lawyers with simple eloquence: "Tell the Court I love my wife, and it is just unfair that I can't live with her in Virginia." The couple rarely attended the legal proceedings, preferring to remain out of the public eye. Yet their quiet determination to live together in their home state would challenge America's racist foundations.

When their case reached the Supreme Court, Virginia's attorneys argued that the law served legitimate purposes, including "preservation of racial integrity" and prevention of "a mongrel breed of citizens." The ACLU countered that such laws were rooted in white supremacy and violated both the Equal Protection Clause and the fundamental right to marry. On June 12, 1967, exactly nine years to the day after their arrest, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in favor of the Lovings, striking down all anti-miscegenation laws nationwide and affirming marriage as "one of the basic civil rights of man."

The Lovings finally returned home to Virginia, building a house just miles from where they grew up. Their victory invalidated similar laws in sixteen states and legalized interracial marriage throughout America. Richard would have only eight years to enjoy this freedom before dying in a car accident in 1975. Mildred, who never remarried, said years later, "I think marrying who you want is a right no man should have anything to do with. It's a God-given right." The day became known as Loving Day, celebrated annually by multiracial families across America as a testament to love's power to overcome legal discrimination.

Historical Context

In 1967, when the Loving case reached the Supreme Court, anti-miscegenation laws remained on the books in sixteen states, primarily in the South. These laws represented one of the last legally sanctioned racial barriers in the United States, even after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 had outlawed discrimination based on race in public accommodations and employment. The Virginia statute specifically prohibited whites from marrying anyone classified as "colored" and carried penalties including prison sentences of up to five years.

America's legal barriers against interracial marriage had deep historical roots dating back to colonial times, with Maryland passing the first such law in 1664. Following the Civil War and the end of slavery, many states actually strengthened their prohibitions as part of the broader Jim Crow legal framework designed to enforce racial segregation and white supremacy. The Supreme Court had previously upheld such laws in the 1883 Pace v. Alabama decision, ruling that anti-miscegenation statutes did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment's equal protection clause because they punished both white and Black participants equally. This "equal application" theory provided the legal foundation that allowed these discriminatory laws to persist into the latter half of the 20th century.

Did You Know?

The term "miscegenation" was coined in 1863 by two Democratic journalists who anonymously published a hoax pamphlet during the Civil War, falsely claiming that Republicans supported racial intermarriage. The term replaced "amalgamation" in legal and social discourse.

When the Lovings won their case in 1967, 16 states still had anti-miscegenation laws. The last known conviction for interracial marriage occurred in 1965 in Florida, where a white woman and a Black man were sentenced to 30 days in jail.

Chief Justice Earl Warren, who wrote the unanimous opinion in Loving v. Virginia (1967), also authored the landmark Brown v. Board of Education (1954) decision that ended legal school segregation.

According to Gallup polls, public approval of interracial marriage was 4% in 1958 when the Lovings married, reached 20% by 1967 when their case was decided, and did not exceed 50% until 1997.

The Lovings' legal victory invalidated anti-miscegenation laws in 15 other states: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia. This affected roughly one-third of the U.S. population at the time.

Today’s Reflection

"Tell the Court I love my wife, and it is just unfair that I can't live with her in Virginia."

These words from Richard Loving, a white man married to a Black woman in 1950s America, cut through legal complexity to the heart of the matter: the injustice of laws that criminalized interracial marriage. His quiet determination helped dismantle statutes rooted in racial prejudice, not divine design.

Scripture speaks plainly to such matters. James writes: "If you really keep the royal law found in Scripture, 'Love your neighbor as yourself,' you are doing right. But if you show favoritism, you sin and are convicted by the law as lawbreakers." James 2:8-9 (NIV)

James doesn't mince words. Favoritism isn't a minor oversight; it's sin. It violates the royal law—the command to love others as ourselves.

When we elevate some and diminish others based on external factors, we betray the very heart of God's law.

This isn't merely about social etiquette; it's about spiritual integrity. Our actions toward others reflect our understanding of God's character. If we believe every person bears God's image, then partiality becomes a theological contradiction.

Consider the rationale once used to uphold segregation: "Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents." Such statements cloak human prejudice in divine language, distorting Scripture to justify sin.

When we manipulate God's Word to endorse our biases, we reveal a heart not fully transformed by the gospel.

Discrimination, therefore, is not just a societal issue; it's a discipleship issue. Our treatment of others mirrors our theology. If we truly grasp that we were all spiritual paupers until Christ clothed us in His righteousness, how can we then elevate some while despising others?

Paul echoes this in his letter to the Ephesians: "For he himself is our peace, who has made the two groups one and has destroyed the barrier, the dividing wall of hostility." Ephesians 2:14 (NIV)

Christ's sacrifice dismantled divisions, uniting Jews and Gentiles into one body. Any attempt to rebuild these walls—be they racial, cultural, or social—stands in opposition to His reconciling work.

So, what does this mean for us today? Our spiritual maturity isn't measured solely by religious activities but by our capacity to love without discrimination. Authentic faith sees others through heaven's eyes, recognizing the divine image in every face.

James challenges us to self-examination: "Do we listen more attentively to some voices than others? Do we make assumptions about people based on their appearance, accent, or background?"

These aren't peripheral questions; they're central to our spiritual journey. True faith produces impartial love, reflecting God's character rather than cultural preferences.

Let us, then, commit to treating discrimination as the discipleship issue it truly is. May we ask God to reveal and uproot any partiality in our hearts, transforming our vision to see others as He does.

For in the end, our capacity to love without favoritism may be the truest measure of how deeply we've understood the gospel itself.

Practical Application

Examine the systems and institutions you participate in this week. Look beyond personal relationships to consider your workplace, church, community organizations, or social circles. Are there patterns of exclusion or favoritism that you've accepted as normal? Consider where you hold influence or decision-making power, however small. Do you consistently amplify certain voices while others remain unheard? Challenge yourself to identify one specific area where you can actively work against partiality. This might mean advocating for equitable policies, questioning hiring practices, or examining how resources and opportunities are distributed in your sphere of influence. The goal isn't superficial diversity but genuine examination of whether your actions reflect God's impartial character in systems that shape other people's lives.

Closing Prayer

Heavenly Father, we thank You for Your perfect love that sees beyond all human divisions and categories. We confess that too often we have treated partiality as a minor fault rather than the sin that it is. Forgive us for the ways we have failed to see Your image in every person we encounter.

Lord, search our hearts and reveal to us the places where favoritism has taken root. Transform our vision so we can see others as You see them. Help us to recognize that our spiritual growth cannot be separated from how we view and treat those different from ourselves. Give us courage to confront bias in our hearts and in our communities. May Your royal law of love govern every aspect of our lives, and may our discipleship be marked by an ever-expanding capacity to love across every human boundary, just as Christ has loved us. In Jesus' name we pray, Amen.

Final Thoughts

The Christian journey is not just about personal piety but about allowing God to transform how we see every human being. When we view others through heaven's eyes, the barriers we've constructed between "us" and "them" begin to crumble. True spiritual maturity is revealed not in our religious activities but in our capacity to love indiscriminately, recognizing the divine image in faces that look nothing like our own.

Also On This Date In History

June 12 - Reagan Challenges Gorbachev to Tear Down Wall

This is the day US President Ronald Reagan challenged Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev to "tear down" the Berlin Wall in 1987.

Author’s Notes

I know there have been more reposts than new posts lately. While some have been updated or lightly rewritten, they’re still—at their core—reflections originally published last year. To my longtime readers, thank you for your patience. To those who are newer, I hope you’re enjoying the work we’re building together.

If you’ve been with me for a while, you know the time and energy it takes to write and post daily. I’ve kept that rhythm for nearly 18 months. Even so, I haven’t stopped. Today’s article and devotional are brand new—as are the next several.

I’m still here. Still writing. And I’ll continue to share new work as time, health, and recovery allow. I have a LASIK touch-up procedure scheduled for this morning, so your prayers are appreciated.

As always, thank you for your continued support and grace.

If you’ve made it this far down the page can you do me a favor? Let me know what you thought about today’s newsletter. Leave a comment or like (❤️) this post. I would really appreciate it.