May 22 - Wagons West: The Birth of America’s Epic Oregon Trail Migration

Moving Forward By Letting Go

This is the day the first major wagon train of approximately 1,000 pioneers departed Independence, Missouri to journey westward on the Oregon Trail in 1843.

In today's lesson, we will explore how the pioneer experience of the first major Oregon Trail migration mirrors our own spiritual journeys. What does it mean to step out in faith when the destination is unclear? How do we find the courage to leave behind what's familiar to pursue God's calling? Join us as we discover how the path of faith always begins not with arrival, but with the holy act of departure.

"By faith Abraham, when called to go to a place he would later receive as his inheritance, obeyed and went, even though he did not know where he was going." - Hebrews 11:8 (NIV)

This Date in History

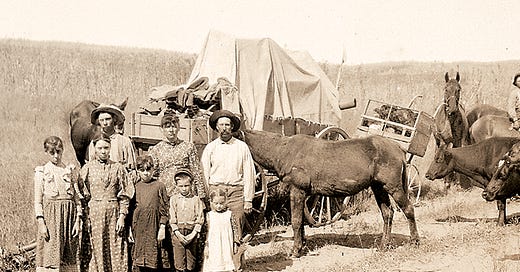

Jesse Applegate squinted against the morning sun as he surveyed the massive gathering at Elm Grove, a small frontier settlement twelve miles west of Independence, Missouri. Nearly a thousand souls stood ready with their earthly possessions packed into one hundred wagons. Children darted between draft animals while mothers called after them, and men discussed the journey in hushed, determined tones. For two years, Applegate had dreamed of Oregon's fertile valleys after hearing tales of its temperate climate and abundant land. Now, on May 22, 1843, he and hundreds of others were about to gamble everything on a dangerous 2,000-mile journey through wilderness to reach that promised land.

The gathering represented a cross-section of America's frontier spirit. Farmers crushed by economic depression in the Mississippi Valley stood alongside adventurers, merchants, and families searching for a fresh start. They came from Missouri, Illinois, Kentucky, Iowa, and beyond, drawn together by what contemporaries called "Oregon Fever"—an almost religious fervor sparked by glowing reports from missionaries and traders who had already made the journey west. All had forsaken the comfort of established homes for the uncertain promise of 640 acres of free land in a territory still disputed between Britain and the United States.

For weeks, the emigrants had been trickling into Independence, the bustling frontier town that served as the gateway to the West and the primary jumping-off point for the Oregon Trail. They purchased supplies, formed traveling parties, and sought advice from experienced guides. Many had sold farms and businesses for a fraction of their worth to finance the journey. Those with means brought several wagons, while poorer families pooled resources and shared expenses. The wagons themselves were modified farm vehicles, often called "prairie schooners" for their canvas covers resembling ship sails, their beds sealed like boats to ford rivers, loaded with food supplies calculated to last six months, along with essential tools, seeds, and family heirlooms too precious to abandon.

The journey ahead would follow paths established by fur traders and explorers since the 1820s, but never before had so many attempted the route together in wagons. The travelers faced an arduous trek across the Great Plains, through the Rocky Mountains via South Pass, across the high desert of the Great Basin, through the Blue Mountains, and finally down to the Columbia River and the Willamette Valley. They knew they would need to average 15 miles per day to reach Oregon before winter snows made mountain passages impassable. Food and water would often be scarce along the way, forcing them to hunt, forage, and rely on occasional trading posts for supplies.

Marcus Whitman, a missionary who had already established a mission in Oregon, joined the travelers at the Platte River. His encouragement proved crucial when Hudson's Bay Company representatives at Fort Hall warned that wagons couldn't make it through the rugged Blue Mountains. "We can build roads where none exist," Whitman insisted, convincing the pioneers to press on with their wagons rather than abandon them for pack animals. This determination to forge new paths rather than accept conventional limitations embodied the spirit of the entire expedition.

The journey that began that May morning would prove arduous beyond imagination. The emigrants faced treacherous river crossings, scorching deserts, mountain passes, and the constant threat of disease. Cholera, dysentery, and other illnesses would claim lives along the way. The weather remained unpredictable, with sudden storms, blistering heat, and early frosts all posing potential dangers. Yet these pioneers persisted, driven by a vision of a better future in Oregon's Willamette Valley. They traveled in a democracy of necessity, electing leaders, establishing rules, and making decisions collectively as they moved steadily westward.

By October, most of the emigrants had reached their destination, forever changing the demographic balance in Oregon Country and strengthening American claims to the territory. Their success encouraged thousands more to follow in subsequent years, transforming the Oregon Trail into America's great migration route. Between 1843 and 1869, when the first transcontinental railroad was completed, an estimated 400,000 settlers would travel this trail, establishing new communities and expanding American influence throughout the region. What Jesse Applegate and his fellow travelers started that spring day became a defining movement in American history—opening the Pacific Northwest to American settlement and embodying the nation's belief in its manifest destiny to span the continent.

Historical Context

The pioneers' decision to embark on this perilous journey in 1843 was influenced by multiple converging factors. America was struggling through the lingering effects of the Panic of 1837, a severe economic depression that left many farmers and merchants desperate for new opportunities. Land in the established states had become increasingly expensive and depleted from years of intensive cultivation, making Oregon's reports of fertile soil and mild climate particularly appealing. Additionally, Senator Lewis Linn of Missouri had introduced legislation promising 640 acres free to each white settler in Oregon, compared to the standard 160 acres available through other land programs in the United States.

Oregon Country at this time remained under joint British-American occupation according to an 1818 treaty, creating a unique legal environment where neither nation exercised exclusive control. The Hudson's Bay Company had established commercial dominance in the region, but American missionary settlements had begun to create a foothold for U.S. interests. This Great Migration of 1843 significantly altered the balance of power, as American settlers soon outnumbered British subjects in the territory. The successful completion of this journey demonstrated that families could make the trek with wagons, effectively opening the floodgates for American emigration that would ultimately lead to the 1846 Oregon Treaty establishing the border at the 49th parallel and securing American claims to the territory.

Did You Know?

Dr. Marcus Whitman, who encouraged the emigrants to continue with their wagons past Fort Hall, would be killed along with his wife Narcissa and 11 others just four years later in 1847 during the Whitman Massacre, a tragic event stemming from cultural misunderstandings and a measles epidemic that devastated the Cayuse tribe.

Jesse Applegate, one of the prominent members of the 1843 migration, later wrote "A Day with the Cow Column in 1843," considered one of the most important firsthand accounts of the Oregon Trail experience, describing the daily routines and challenges of managing livestock during the journey.

Although often romanticized as a journey of covered wagons, most emigrants actually walked alongside their wagons to spare their draft animals from additional weight. A typical traveler would walk over 2,000 miles, wearing out several pairs of boots or shoes during the journey.

The Oregon Trail was not a single, well-defined route, but rather a broad network of trails. While there was a main route followed by many emigrants, numerous cutoffs and alternate trails developed over time—such as the Barlow Road, Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff, and Applegate Trail—based on conditions, geography, and final destinations.

Independence Rock in Wyoming became known as the "Great Register of the Desert" because so many pioneers carved their names into it as they passed. Reaching this landmark by July 4th was considered crucial timing, as it meant travelers were on schedule to cross the mountains before winter snows made passage impossible.

Today’s Reflection

The first wagon train to Oregon didn't begin with the promise of the destination. It began with the parting. Before they could arrive, they had to let go. They had to choose to leave behind everything familiar.

On May 22, 1843, nearly a thousand souls stepped away from homes, communities, and security into a 2,000-mile journey toward an unknown future. The promise of fertile valleys pulled them forward, but their first step wasn't just toward Oregon. It was away from Missouri.

This echoes the spiritual journey God calls each of us to take.

"By faith Abraham, when called to go to a place he would later receive as his inheritance, obeyed and went, even though he did not know where he was going." Hebrews 11:8

Faith doesn't always, or even usually, begin with clarity. It begins with displacement. It begins with the discomfort of letting go before we fully understand what comes next. Abraham didn't move toward a promise without cost. He first had to release his grip on what he knew. When God called, Abraham didn't wait for a map. He responded to a voice. And he trusted it would be enough.

The Oregon pioneers understood this kind of surrender. Many sold homes for a fraction of their value, said goodbye to loved ones, and placed their futures in the balance. Some were driven by opportunity, others by ambition. But all shared in that fundamental, deeply human act: leaving behind the known for the sake of something more.

Faith, at its core, begins with surrender before it bears fruit.

We celebrate the outcomes of faith such as miracles, blessings, and breakthroughs. But Scripture reminds us: the real beginning is the letting go. Moses left Midian. David stepped onto a battlefield. The disciples dropped their nets and walked away from their families. None had a full picture. They had only the call of the One who goes ahead.

Our walk with God is rarely lit by a full blueprint. More often, it's lit step by step, like travelers guided by landmarks rather than maps. We move forward by trust, not by sight.

"Therefore do not worry about tomorrow, for tomorrow will worry about itself." Matthew 6:34

God does not offer us control. He offers us Himself. And His presence is enough.

The pioneers faced hardship: rivers, mountains, sickness, loss. But they kept going—not because they were certain of success, but because they were committed to the journey. And our faith is tested the same way. Not in comfort, but in perseverance when the outcome is unclear. That's where faith is forged. That's where we discover if we're visiting belief or abiding in it.

But they didn't go alone.

They formed communities, shared burdens, and found strength together. The same is true for us. We are not meant to walk this path by ourselves.

"Let us consider how we may spur one another on toward love and good deeds, not giving up meeting together…" Hebrews 10:24-25

We need companions who remind us of the promise, walk beside us when we falter, and carry hope when we cannot.

Along the trail, pioneers marked their progress with landmarks. These weren't endpoints, but signs that they were still on the right path. In our lives, God gives us moments like this too—answered prayers, deep peace, quiet assurance. They don't show the whole journey, but they tell us He's still leading.

So what is God calling you to release today?

Comfort? Control? A dream, a fear, a false sense of safety?

Abraham couldn't inherit God's promise while clinging to Ur. And the pioneers couldn't reach the Willamette Valley while staying in Missouri. The same is true for us.

But here's the difference.

They followed rumors and maps drawn by strangers. We follow a faithful God whose voice still speaks, whose promises never fail.

The journey may be long. The path may wind. But He walks with us. And in every act of surrender, we are not just leaving behind the old, we are stepping into deeper communion with the One who calls us.

The destination makes the displacement worthwhile.

The pioneers gave up everything for a land they had never seen. Abraham journeyed toward a promise he would only glimpse, trusting that what God had spoken was enough.

That's the essence of faith—not seeing the whole path, but believing the One who calls us forward.

So the question remains: will you trust Him enough to release what is familiar, even if the road ahead feels uncertain? Will you loosen your grip on what is safe in order to take hold of what is sacred?

Because the journey of faith never begins at the finish line. It begins with a call, a departure, and the quiet courage to say yes—before the details are clear, before the outcome is known, and before the reward is in sight.

Practical Application

Create a personal "Independence Rock" in your faith journey by writing down specific moments when God has proven faithful in your past. Like the pioneers who carved their names on Independence Rock to mark their progress, documenting these spiritual milestones serves as a concrete reminder that you're on the right path. Then, identify one area where God is calling you to "leave Egypt" and step into the unknown. This might be a relationship, habit, comfort zone, or belief that you need to surrender. Take one tangible step this week to release your grip on this area. Finally, ask yourself what provisions you need for the journey ahead. The Oregon Trail pioneers carefully prepared; likewise, determine what spiritual resources you need to cultivate now (prayer disciplines, Scripture knowledge, community connections) to sustain you through future challenges.

Closing Prayer

Faithful God, thank You for calling us out of comfortable places into deeper relationship with You. We acknowledge our fear of the unknown and our tendency to cling to what feels safe and familiar. Give us the courage of Abraham, who followed Your voice without seeing the full journey ahead. Help us to release our grip on those things we've made into false securities, trusting instead in Your unfailing promises.

Lord, we ask for companions on this journey of faith, fellow travelers who will encourage us when the path seems difficult. When obstacles arise, strengthen our resolve to continue forward. Guide us with Your Spirit, marking our way with glimpses of Your presence. Thank You that we don't walk alone but that You go before us, beside us, and behind us. May we honor You with each step of faith and find joy in the journey itself, not just the destination. In Jesus' name, Amen.

Final Thoughts

Faith is not the absence of uncertainty but the presence of trust in the midst of it. When we cannot trace God's hand, we can still trust His heart. The most transformative journeys of our lives will rarely come with complete clarity at the outset. Instead, they begin with a single step taken in the direction of God's voice, leaving behind what is familiar for what is faithful, what is comfortable for what is called.

If you’ve made it this far down the page can you do me a favor? Let me know what you thought about today’s newsletter. Leave a comment or like (❤️) this post. I would really appreciate it.

Epic reminder that faith is not blind, but trusting. Thx.

Thanks Jason, it’s always hard to leave what we know. The devil we know always seems safer than the unknown. Whether spiritual or physical, do we desire most of all to be faithful and free?To live in the now, we must be willing to live on the edge without the safety net of the known.