March 9 - Wrongful Execution: The Truth About the Jean Calas Affair

Examining Our Hearts for Religious Prejudice

This is the day in 1765 when Jean Calas, having been tortured and executed in 1762 on charges of murdering his son, was posthumously exonerated by judges in Paris following a public campaign by the writer Voltaire.

In today's lesson, we will explore how religious prejudice disguised as righteousness led to the wrongful execution of Jean Calas in 18th century France. How often do we also judge other believers through the lens of our own traditions? What does Christ's prayer for unity require of us when encountering Christians different from ourselves?

"My brothers and sisters, believers in our glorious Lord Jesus Christ must not show favoritism." - James 2:1 (NIV)

This Date in History

The judges' verdict thundered through the packed Paris courtroom, reversing a grave injustice that had shocked the conscience of France. Jean Calas, a Protestant merchant from Toulouse, had been brutally tortured on the wheel and executed three years earlier for allegedly murdering his own son to prevent his conversion to Catholicism. Now, on March 9, 1765, the court declared him innocent, too late to save his life but not too late to restore his honor and expose the religious prejudice that had condemned him.

Behind this remarkable reversal stood one of history's most influential writers. Voltaire, already famous throughout Europe for his philosophical works, had taken up Calas's cause after learning details that suggested a terrible miscarriage of justice. When Marc-Antoine Calas was found dead in his father's home in 1761, authorities immediately suspected murder rather than suicide, driven by anti-Protestant sentiment in Catholic Toulouse. Despite no material evidence and the family's consistent testimony that Marc-Antoine had taken his own life after gambling losses, Jean Calas was arrested, tried, and sentenced to death.

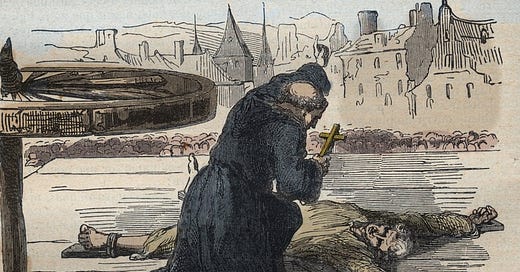

The execution itself was designed to extract a confession through excruciating pain. Jean Calas endured having each limb broken by an iron bar before being strangled on a wooden wheel. Throughout his torture, even in his final moments, the 64-year-old merchant maintained his innocence, declaring: "I die innocent. Jesus Christ, who was innocence itself, was willing to die an even more cruel death."

Voltaire, upon hearing these details from a traveler while at his estate near Geneva, became immediately suspicious of judicial murder motivated by religious hatred. Though initially knowing little about the Calas family, he launched into action, writing letters to influential contacts across France and publishing pamphlets questioning the verdict. "I saw that this was not merely a judicial error," he later wrote, "but a religiously motivated murder committed with the sword of justice."

The philosopher dedicated nearly three years to the case, interviewing witnesses, gathering documentation, and writing scathing critiques of religious fanaticism. His 1763 "Treatise on Tolerance," inspired by the Calas affair, became a foundational text for religious freedom. Voltaire personally financed the legal efforts to reopen the case and supported the Calas widow and remaining children, who had been scattered and impoverished by the proceedings.

The Council of State in Paris finally agreed to review the case in June 1764. After months of new testimony and examination of the original trial records, forty judges unanimously declared Jean Calas innocent on March 9, 1765. They ordered the Toulouse parliament to annul its judgment and rehabilitate Calas's memory. The French king granted the family 36,000 livres in compensation, a significant sum acknowledging the gravity of the injustice.

The victory represented more than justice for one family. It marked a turning point in French legal history and catalyzed growing calls for judicial reform. The case exposed fatal flaws in a system where torture was used to extract confessions and where religious prejudice could override evidence. Voltaire, already 70 years old, considered the Calas vindication among his greatest achievements.

For the remaining thirteen years of his life, Voltaire would continue to champion other victims of judicial and religious persecution, including Pierre-Paul Sirven and the Chevalier de La Barre. The Calas case established a template for intellectual activism against injustice that would influence generations of writers and reformers. When Voltaire made his triumphant return to Paris shortly before his death in 1778, many who cheered him remembered him first as the man who had saved the honor of Jean Calas and struck a blow against religious persecution.

Historical Context

In 18th century France, religious tensions formed a turbulent undercurrent throughout society. The Catholic Church dominated religious and political life since the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, which had previously granted French Protestants (Huguenots) certain civil rights. Protestants lived as second-class citizens, unable to legally marry, inherit property, or practice their faith openly. Their deaths could not be properly recorded, and they were often denied proper burial.

This period also witnessed the rise of Enlightenment thinking across Europe, challenging traditional authorities and advocating for rational inquiry and tolerance. Thinkers like Voltaire, Montesquieu, and Rousseau questioned established religious and political institutions. Their works, although frequently censored, circulated widely among the intellectual elite and gradually influenced broader societal attitudes. The Calas case emerged at this critical juncture, exemplifying both the persistent religious prejudices of the old order and the growing intellectual resistance against such intolerance that would eventually contribute to revolutionary changes throughout French society.

Did You Know?

Jean Calas's case inspired one of the first organized humanitarian campaigns in European history, with Voltaire using an unprecedented multi-pronged approach of private lobbying, public pamphlets, and international pressure to force a judicial review.

The Toulouse judges who condemned Jean Calas had relied heavily on "public knowledge" as evidence, including rumors that Marc-Antoine had been seen attending Catholic services, which were later found to be unsubstantiated.

Prior to championing Calas's cause, Voltaire had expressed anti-Protestant sentiments in some of his writings, making his passionate defense of the Calas family a notable shift in his views on religious tolerance.

The Calas case contributed to discussions on judicial reform in France, and in its aftermath, King Louis XV reinforced the requirement that all death sentences receive royal confirmation before execution.

After Jean Calas's exoneration, his daughter Anne became a companion to Marie Corneille, a protégée of Voltaire, and lived under his protection at Ferney until her marriage—showing Voltaire's personal commitment beyond the public campaign.

Today’s Reflection

Jean Calas stood falsely accused, tortured, and executed by those who believed they were defending the true faith. The judges and citizens of Toulouse didn't see themselves as villains but as protectors of religious truth, convinced that a Protestant father would naturally murder his son to prevent his conversion to Catholicism. Their religious prejudice didn't appear to them as hatred but as righteous certainty, a blindness that cost an innocent man his life.

"My brothers and sisters, believers in our glorious Lord Jesus Christ must not show favoritism" James 2:1 (NIV) speaks directly to this dangerous tendency within all our hearts.

Religious division has marked Christian history since its earliest days. The disciples themselves fell into this trap when they encountered someone casting out demons who wasn't part of their group.

"Master," said John, "we saw someone driving out demons in your name and we tried to stop him, because he is not one of us." But Jesus immediately corrected this tribal thinking: "Do not stop him, for whoever is not against you is for you" Luke 9:49-50 (NIV).

Jesus challenged their assumption that only those within their circle could properly represent Him or do His work.

This same spirit of exclusion continues today whenever we quietly assume our particular denomination, worship style, or theological stance represents the "true" version of Christianity. We might not torture or execute others like those in 18th century France, but we can execute their character, question their salvation, or dismiss their faith as inferior. The subtlety of this prejudice makes it particularly dangerous because it often masquerades as doctrinal purity or theological precision rather than what it truly is: spiritual pride.

Jesus consistently modeled a different approach. He reached across religious and cultural divides, engaging with Samaritans despite centuries of religious hostility between Jews and Samaritans. He praised the faith of Roman centurions and Canaanite women. He challenged religious leaders who had turned faith into an exclusionary system of rules rather than a relationship with God.

His ministry was marked by breaking down barriers that religious people had carefully constructed to separate the "righteous" from the "unrighteous."

The apostle Peter had to learn this lesson through divine intervention. Deeply committed to Jewish religious traditions, Peter needed a vision from God before he could overcome his prejudice against Gentiles. The revelation transformed him: "I now realize how true it is that God does not show favoritism but accepts from every nation the one who fears him and does what is right" Acts 10:34-35 (NIV).

Peter's heart changed when he realized God's kingdom was far more inclusive than his religious tradition had led him to believe.

Examining our hearts for religious prejudice requires painful honesty. Do we quietly judge believers from other denominations or traditions? Do we assume our way of worshiping is superior? Do we place denominational identity above our shared identity in Christ? The Toulouse judges were certain they stood for righteousness, yet their certainty blinded them to the innocent man before them.

Religious prejudice rarely announces itself; it hides within our assumptions about who truly belongs in God's family.

What will you do when confronted with believers who worship or practice their faith differently than you do? Will you, like the Toulouse judges, condemn what you don't understand? Or will you, like Voltaire, challenge your own preconceptions and defend the dignity of those outside your circle?

Jesus prayed for unity among His followers, not uniformity. His prayer wasn't that we would all agree on every theological point, but that our love for one another would testify to the world of His reality. Will you choose to see beyond denominational labels to recognize fellow members of Christ's body?

Practical Application

Set aside time this week for honest self-reflection about your religious attitudes. Write down three Christian groups or denominations you find most difficult to understand or accept. For each one, list specific beliefs or practices you appreciate about them, noting how these might enrich your own faith journey. Next, identify one specific way you've judged others based on religious differences. Commit to engaging with someone from a different Christian tradition this month, not to debate theology but to listen and learn about their personal faith journey, asking how they experience God's presence in their lives.

Closing Prayer

Lord God, we thank You for the courage of those who stand against prejudice and fight for justice, even for those different from themselves. Forgive us for the times we've allowed religious pride to blind us to Your work in other believers' lives. Open our eyes to see beyond denominational divisions to recognize the authentic faith You honor in all who truly follow You. Help us to examine our hearts honestly, rooting out the subtle prejudices that separate us from our brothers and sisters in Christ. Give us the humility to admit when we've elevated our traditions above Your command to love one another. May our unity in Christ become a powerful testimony of Your love to a divided world. In Jesus' name, Amen.

Final Thoughts

The tragic story of Jean Calas reminds us how righteousness can become a disguise for prejudice when we're convinced we alone possess the truth. Just as Voltaire had to overcome his own anti-Protestant views to champion justice, we too must examine our hearts for subtle religious biases that divide Christ's body. God's kingdom transcends our denominational boundaries, calling us to recognize His work in places and people we might otherwise dismiss.

THIS IS THE DAY Last Year

Today's historical event is the same as last year's publication, but it includes new details and insights for a richer perspective. The Reflection offers an entirely new lesson.

Author’s Notes

If you’ve been enjoying these devotionals and want to help ensure they continue, now is a great time to become a paid subscriber.

Through March 14, I’m offering 20% off, bringing the cost down to just $4 a month or about $1 a week for seven devotionals every week. While everything remains free for all subscribers, paid support makes this work possible.

If you’ve been thinking about it, this is a great way to contribute!

This devotional is free to read. You can support this publication by becoming a subscriber, upgrading to paid subscriber status, liking (❤️) this post, commenting, and/or sharing this post with anyone who might enjoy it. You can also make a ONE-TIME DONATION in any amount. Thank you for your support!

I was a bit shocked when I first read about this years ago, seemed way out of place by late 18th century France.

Fun fact regarding how much change followed it, a mere decade and a half later, the Protestant banker Necker became the finance minister of King Louis XVI, and became so popular his dismissal in the summer of 1789 was one of the moments when the Parisians turned against the royal government.

Despite reading Voltaire in school, I had never heard of this. What a tremendous story and lesson for us all! Right on target!