April 11 - The Elephant Man: Joseph Merrick’s Unique Path to Dignity

Finding Divine Purpose in Physical Limitations

This is the day Joseph Merrick, known as the "Elephant Man," died in London in 1890.

In today's lesson, we will examine the extraordinary life of Joseph Merrick, known as the "Elephant Man," whose physical deformities masked a gentle and dignified soul. What does it mean to trust God's purpose when our formation seems flawed by human standards? How might our greatest limitations become the very vessels through which divine glory shines most brilliantly?

"Does not the potter have the right to make out of the same lump of clay some pottery for special purposes and some for common use?" - Romans 9:21 (NIV)

This Date in History

Joseph Merrick sat alone in his room at the Royal London Hospital, carefully folding paper into intricate shapes. His gnarled, misshapen hands moved with surprising dexterity as he completed another model cathedral, adding it to his collection. For this man, whose severe physical deformities had subjected him to a lifetime of ridicule and exploitation, these quiet moments of creation offered rare peace. He'd found sanctuary here after years of being exhibited as a human curiosity, yet Merrick knew his condition was worsening. "I sometimes wish I could sleep like normal men," he confided to his physician and friend, Dr. Frederick Treves.

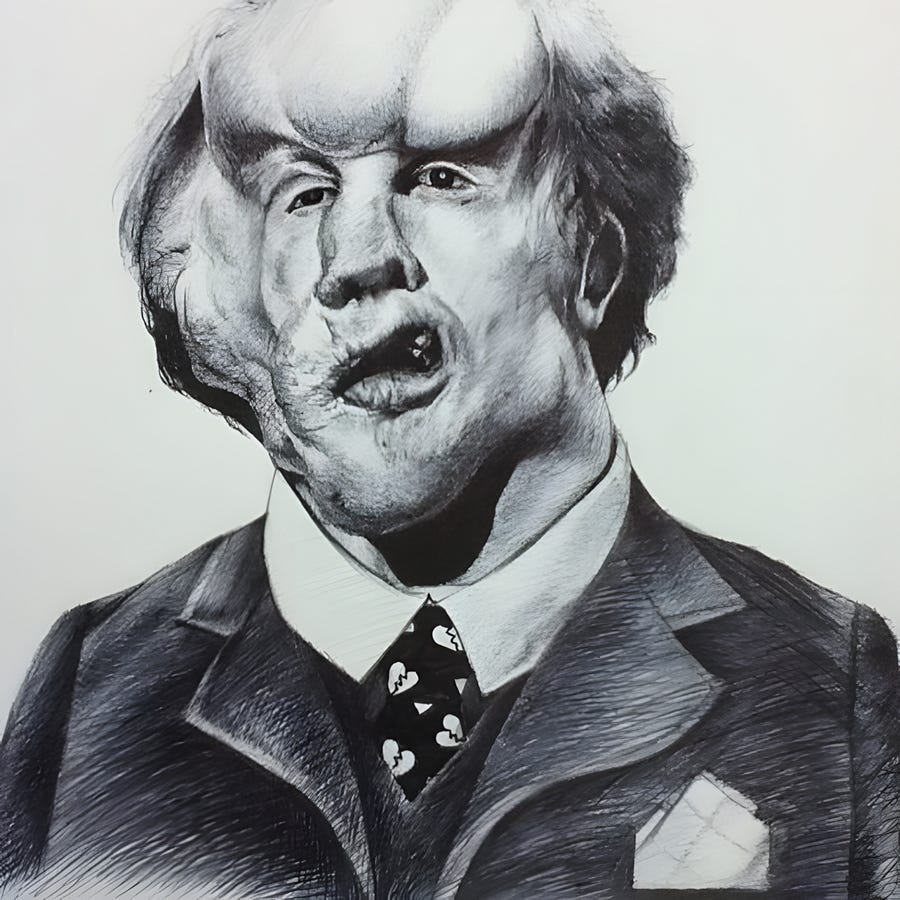

Born in Leicester in 1862, Merrick's early life gave no indication of the hardships that awaited him. His body began changing dramatically around age five, developing large, lumpy protrusions across his skin. His right arm and both legs grew disproportionately, while thick, cauliflower-like growths and loose folds of skin distorted his face beyond recognition. As his condition progressed, Merrick's speech became increasingly difficult to understand, though his intellect remained entirely intact. His mother's death when he was eleven removed his strongest advocate, and his father and stepmother soon forced him from home. After failing at various jobs due to his appearance, Merrick entered the Leicester Union Workhouse at 17, where he spent four miserable years.

Desperate for escape from the workhouse's grim conditions, Merrick contacted showman Sam Torr and willingly became an exhibition attraction. He was displayed as "The Elephant Man: Half-Man, Half-Elephant" in traveling freak shows throughout England. Merrick's exhibit card, which he helped write, stated: "Ladies and Gentlemen... I am not ill-formed but ill-formed that I may earn a living." When regulations against human exhibitions tightened in England, Merrick traveled to continental Europe, but was robbed by his road manager and abandoned in Brussels. He somehow made his way back to London, arriving at Liverpool Street Station with nothing but the clothes on his back.

It was at this lowest point in 1886 that destiny intervened. Nearly four years earlier, surgeon Frederick Treves had briefly examined Merrick for medical purposes but lost track of him. Now, police officers found Treves' card among Merrick's few possessions and contacted the doctor. Treves immediately recognized Merrick and arranged accommodation at the London Hospital, where administrators, moved by his plight, provided him permanent residence. For the first time, Merrick experienced genuine kindness and dignity. Hospital staff treated him not as a curiosity but as a human being deserving of respect. Treves later wrote, "As a specimen of humanity, Merrick was ignoble and repulsive; but the spirit of Merrick, if it could be seen in the form of the living, would assume the figure of an upstanding and heroic man."

In his hospital quarters, Merrick blossomed. He read voraciously, created artistic models, and wrote letters and poetry. Treves introduced him to distinguished visitors, including Alexandra, Princess of Wales, who initiated a correspondence with him. Other aristocratic women visited regularly, giving Merrick his first experiences of female companionship beyond his mother. During a countryside holiday arranged by Treves, Merrick wrote, "I have seen the sun and the sky, and have felt the wind on my face." These simple pleasures, taken for granted by most, were profound joys to a man who had spent most of his life hidden away. Yet his physical condition continued to deteriorate, with his head growing so heavy that he could only sleep sitting up, leaning forward with his head on his knees.

On April 11, 1890, Merrick was found dead in his bed at age 27. The official cause of death was asphyxiation. Treves theorized that Merrick had attempted to sleep lying down "like normal people," causing his head to fall back and dislocate his neck. Though modern researchers suggest he may have died from a stroke or respiratory infection related to his condition (now believed to be Proteus syndrome), the poignancy of Treves' theory persists. In his brief life, Joseph Merrick became a symbol of human dignity in the face of unimaginable adversity, challenging Victorian society's assumptions about physical difference and human worth. His story, immortalized in books, plays, and films, continues to raise questions about how we perceive and treat those who appear different from ourselves.

Historical Context

The treatment of individuals with physical differences in Victorian England reflected the era's complex blend of scientific pursuit, religious morality, and social spectacle. During the 1800s, so-called "human curiosities" were viewed as legitimate entertainment through the lens of both science and showmanship. Freak shows became immensely popular attractions that drew audiences from all social classes, who paid to gaze upon people with unusual physical characteristics. These exhibitions were often presented with pseudoscientific explanations that blurred the line between education and exploitation. By the time of Merrick's exhibition in the 1880s, the practice was beginning to face criticism from medical professionals and social reformers who questioned the ethics of such displays.

The medical profession itself was undergoing significant transformation during Merrick's lifetime. The 1858 Medical Act had standardized qualifications for physicians, while advances in understanding of disease and anatomy were rapidly changing medical practice. London's renowned teaching hospitals, including the Royal London Hospital where Merrick spent his final years, served as centers for medical research and training. Dr. Frederick Treves represented a new generation of medical professionals with more systematic approaches to studying unusual conditions. Yet the medical establishment still struggled with conditions they couldn't fully explain, often categorizing people like Merrick as "monstrosities" or "freaks of nature" in medical textbooks. This tension between scientific curiosity and human compassion characterized the medical response to Merrick's condition, which wouldn't be accurately diagnosed as Proteus syndrome for nearly a century after his death.

Did You Know?

Dr. Frederick Treves initially paid Merrick's showman two pence to examine him medically, and later included clinical photographs of Merrick in his teaching materials without anticipating their future relationship.

Merrick created an intricate cardboard model of Mainz Cathedral despite never having visited it, working only from a postcard picture and using just a penknife as his tool.

In 1980, American physician Michael Cohen identified Merrick's condition as Proteus syndrome, a rare genetic disorder affecting only about one in a million people, finally providing a medical explanation almost a century after his death.

The Royal London Hospital received substantial donations from the public following an appeal by the hospital's chairman, enabling them to provide permanent accommodation and care for Joseph Merrick.

Despite his severe physical deformities, Joseph Merrick possessed normal intelligence and developed a refined appreciation for literature and art during his time at the hospital, demonstrating remarkable resilience and intellectual curiosity.

Today’s Reflection

Joseph Merrick once wrote on his exhibition card, "I am not ill-formed but ill-formed that I may earn a living." Behind these simple words lay profound wisdom from a man whose body subjected him to unimaginable suffering and social rejection.

What strikes most about Merrick's story is not just his physical condition but his refusal to see himself as merely a victim of cruel circumstance. Even in his darkest days, he recognized purpose in his pain.

This perspective echoes the biblical truth found in Romans 9:21 (NIV): "Does not the potter have the right to make out of the same lump of clay some pottery for special purposes and some for common use?" God, the divine Potter, shapes each vessel with intention, even when the design seems bewildering to human understanding.

The mystery of human suffering has challenged believers throughout history. We struggle to reconcile a loving God with the painful realities many people face. Why would God allow someone like Joseph Merrick to endure such severe physical deformities? Why would the Creator permit any child to be born into a life of pain? These questions strike at the heart of faith itself.

The apostle Paul doesn't shy away from this tension in Romans 9, acknowledging the audacity of questioning the Creator's decisions. Romans 9:20 (NIV): "But who are you, a human being, to talk back to God? Shall what is formed say to the one who formed it, 'Why did you make me like this?'" This isn't a dismissal of human questioning but an invitation to humility before mysteries we cannot fully comprehend.

When we examine Merrick's life more closely, we find something remarkable. In the midst of his suffering, his humanity shone brilliantly. His gentle spirit, creativity, and intellectual curiosity challenged Victorian society's assumptions about human worth.

Through him, countless people including Dr. Treves were confronted with their own prejudices and transformed by compassion. The hospital staff who initially recoiled at his appearance came to see the beautiful soul within. Even today, over a century later, his story continues to move hearts and minds.

Like Paul's jars of clay, Merrick's broken body displayed something of immeasurable value within. 2 Corinthians 4:7 (NIV): "We have this treasure in jars of clay to show that this all-surpassing power is from God and not from us."

God's purposes often unfold through unexpected vessels.

Throughout scripture, we see this pattern repeatedly. Moses had a speech impediment yet became God's spokesperson to Pharaoh. David was the overlooked youngest son yet became Israel's greatest king. Paul called himself the "chief of sinners" yet wrote much of the New Testament.

Their stories remind us that God consistently works through what human wisdom would reject. The vessels God chooses often appear cracked, misshapen, or ordinary to human eyes. But those apparent weaknesses become the very spaces where divine power shines most clearly.

What the world sees as brokenness, God uses as breakthrough.

This truth confronts our culture's obsession with physical perfection and productivity. We live in a society that increasingly values people based on appearance, ability, or contribution. From prenatal testing that targets genetic differences to social media filters that erase our flaws, we worship at the altar of perfection.

But God's economy operates by different principles. Every human life carries inherent dignity because we bear the divine image. Every person, regardless of physical appearance, intellectual capacity, or social status, has been fashioned by the Creator's hands.

Our worth comes not from conformity to cultural standards but from the One who formed us with purpose and intention. The question isn't whether we're perfectly formed by human standards but whether we'll allow God to fulfill His purpose through our formation.

The invitation before us today is radical trust. Can we, like Merrick, refuse to be defined by our limitations? Can we embrace our unique formation, even the painful aspects, as part of God's mysterious purpose?

This doesn't mean passively accepting injustice or unnecessary suffering. Jesus himself healed countless people, showing God's desire for human wholeness. But until all is made new, we live in the tension of present suffering and future glory. We are works in progress, clay still being shaped on the Potter's wheel.

The true miracle of Merrick's life wasn't found in medical explanations or public fascination but in his quiet dignity that transcended his circumstances. His life calls us to stop questioning our formation and start fulfilling our purpose, whatever vessel we may be.

Where in your life have you resisted God's formation? What aspects of yourself have you labeled as mistakes rather than materials for the Master Potter?

The challenge before us is surrendering to the Potter's hands, trusting that He creates with purpose, even when that purpose remains hidden from our understanding. This surrender doesn't promise freedom from suffering but offers freedom within it.

Today, may we echo Merrick's wisdom, declaring over our lives, "I am not ill-formed, but formed for glory." May we trust that the same hands that formed stars and mountains have shaped our lives with equal intentionality. And may we allow our brokenness to become the very places where God's light shines most brilliantly.

Practical Application

Take time to identify an aspect of yourself that you've considered a limitation, weakness, or flaw. Write it down, then deliberately reframe it as a potential vessel for God's purpose by completing this sentence: "This is not a mistake but a material God can use for..." Consider how this characteristic might actually be uniquely suited for specific forms of ministry or compassion toward others. Then create something physical or artistic that represents your reframing, whether a simple drawing, written poem, or small craft using imperfect materials. Keep this creation visible during the coming week as a reminder that our perceived flaws are often precisely where God's light enters most powerfully.

Closing Prayer

Heavenly Father, we thank You for creating each of us with intention and purpose, even when we cannot understand Your divine design. We acknowledge that You are the Master Potter, shaping vessels for Your glory through both our strengths and what we perceive as weaknesses. Lord, forgive us for the times we have questioned Your craftsmanship or rejected parts of ourselves that You lovingly formed. We ask for the courage to see ourselves through Your eyes, recognizing that our limitations often become the very channels through which Your power flows most visibly. Give us Joseph Merrick's quiet dignity and humility to accept our unique formation, trusting that Your purposes unfold even through our most difficult circumstances. Help us surrender completely to Your skillful hands, that we might fulfill the purpose for which we were created. In Jesus' name, Amen.

Final Thoughts

The moments you feel most broken may be precisely when God's light shines most brilliantly through you. What appears as a crack in your vessel is often the very opening through which divine glory pours forth. Never mistake your unique formation for divine negligence. In the Potter's hands, nothing is wasted, nothing is random, and nothing is without redemptive potential. Your worth was established at creation, confirmed at Calvary, and will be fully revealed in eternity. Until then, trust the Potter's hands.

THIS IS THE DAY Last Year

April 11 - Urgent Request: How McKinley Led America Into the Spanish War

This is the day President McKinley asked Congress for a declaration of war against Spain in 1898.

Author’s Notes

This has nothing to do with today’s topic, but I found it fascinating!

This devotional is free to read. You can support this publication by becoming a subscriber, upgrading to paid subscriber status, liking (❤️) this post, commenting, and/or sharing this post with anyone who might enjoy it. You can also make a ONE-TIME DONATION in any amount. Thank you for your support!

Marvelous and poignant. Thank you, Jason.

The story of Mr. Merrick reminds me of how the perfect, incorruptible God-man voluntarily came out of eternity to go to this "place" on behalf of sinners who--without His loving intervention via living the only perfectly righteous, obedient life until His substitutionary atoning death--would be subject to far worse than Mr. Merrick experienced... unto all eternity. (See Luke 16:23-24, e.g.)

Mel Gibson's portrayal, in "The Passion of the Christ," via actor James Caviezel, was alike to the can't-watch-this-horror which Jeff, in his comment, describes some of the students feeling in his communications class. But it was Biblically accurate; and that was only the surface physical stuff which can be portrayed on film.

"His appearance was marred more than any man, and His form more than the sons of men... He has no stately form or majesty that we should look upon Him, nor appearance that we should be attracted to Him." (Isaiah 52:14b,c & 53:2c,d,e)

I saw the movie., "The Elephant Man," when it was first released in 1980, and it left an indelible impact on me. I believe it is a movie everyone should see, and when I was an adjunct professor at Colorado Christian University, I taught a Christian communications class in which I showed this movie as a point of study over the course of three different class periods one week. After the first part of the showing, a couple of students remarked that they didn't want to have to see the rest because it was so difficult emotionally. We did watch the whole movie, and in the end it became a poignant element in the fabric of the class that semester. When Mr. Merrick toward the end of the movie is forced to confront the abusive crowd at the train, he finally turns to them and screams, "I am not an animal! I am a human being!," I broke down and cried, and even as I recall the scene, it bring tears. We are all God's precious creations regardless of looks or otherwise. I eventually became a high school SPED teacher for 16 years, and I still have a special place in my heart for those who may look or act differently only because God, in his sovereignty, made us all the way we are.